Psychological scientists have become increasingly interested in studying the positive life changes that people report in the aftermath of highly stressful life events, including diagnosis with terminal illness, grief, and sexual assault. This notion has been referred to with many different names, but the construct is most commonly referred to by scientists as adversarial growth, posttraumatic growth, stress-related growth, altruism born of suffering and benefit finding.

Growth through Adversity – The Power of Grief

Posttraumatic growth (PTG), usually after some period of loss and grief, aims to capture these positive transformations in beliefs and behavior. PTG may take five forms: improved relations with others, identification of new possibilities for one’s life, increased personal strength, spiritual change, and enhanced appreciation of life. These positive changes relate to the development of important qualities of character, such as diligence, generosity, love, purpose, and humility. Thus, adversity may provide opportunities for the development of important character traits, echoing St. Paul’s insight that:

“suffering produces endurance, and endurance produces character, and character produces hope” (Romans 5: 3-4).

Signs of post-traumatic growth

PTG can be confused with resilience, but the two are different. “PTG is sometimes considered synonymous with resilience because becoming more resilient as a result of struggle with trauma can be an example of PTG—but PTG is different from resilience, says Kanako Taku, PhD, associate professor of psychology at Oakland University, who has both researched PTG and experienced it as a survivor of the 1995 Kobe earthquake in Japan.

Resilience is the personal attribute or ability to bounce back. PTG, on the other hand, refers to what can happen when someone who has difficulty bouncing back experiences a traumatic event that challenges his or her core beliefs, endures psychological struggle (even a mental illness such as post-traumatic stress disorder), and then ultimately finds a sense of personal growth. It’s a process that takes a lot of time, energy and struggle.

Someone who is already resilient when trauma occurs won’t experience PTG because a resilient person isn’t rocked to the core by an event and doesn’t have to seek a new belief system, explains Tedeschi. Less resilient people, on the other hand, may go through distress and confusion as they try to understand why this terrible thing happened to them and what it means for their world view.

To evaluate whether and to what extent someone has achieved growth after a trauma, psychologists use a variety of self-report scales. One that was developed by Tedeschi and Calhoun is the Post-Traumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI) (Journal of Traumatic Stress, 1996). It looks for positive responses in five areas:

The post-traumatic growth inventory

To evaluate whether and to what extent someone has achieved growth after a trauma, psychologists look for positive responses in five areas.

1: Appreciation of life

2: Relationships with others

3: New possibilities in life

4: Personal strength

5: Spiritual change

Source: Richard Tedeschi, PhD, and Lawrence Calhoun, PhD, Journal of Traumatic Stress, 1996

A predisposition for Personal Growth after Grief?

Some researchers have tried to corroborate self-reported growth by questioning friends and family members about whether growth “sticks.” There appear to be two traits that make some more likely to experience PTG: openness to experience and extraversion. That’s because people who are more open are more likely to reconsider their belief systems and extroverts are more likely to be more active in response to trauma and seek out connections with others.

Women also tend to report more growth than men, but the difference is relatively small. Age also can be a factor, with children under 8 less likely to have the cognitive capacity to experience PTG, while those in late adolescence and early adulthood—who may already be trying to determine their world view—are more open to the type of change that such growth reflects, says Tedeschi.

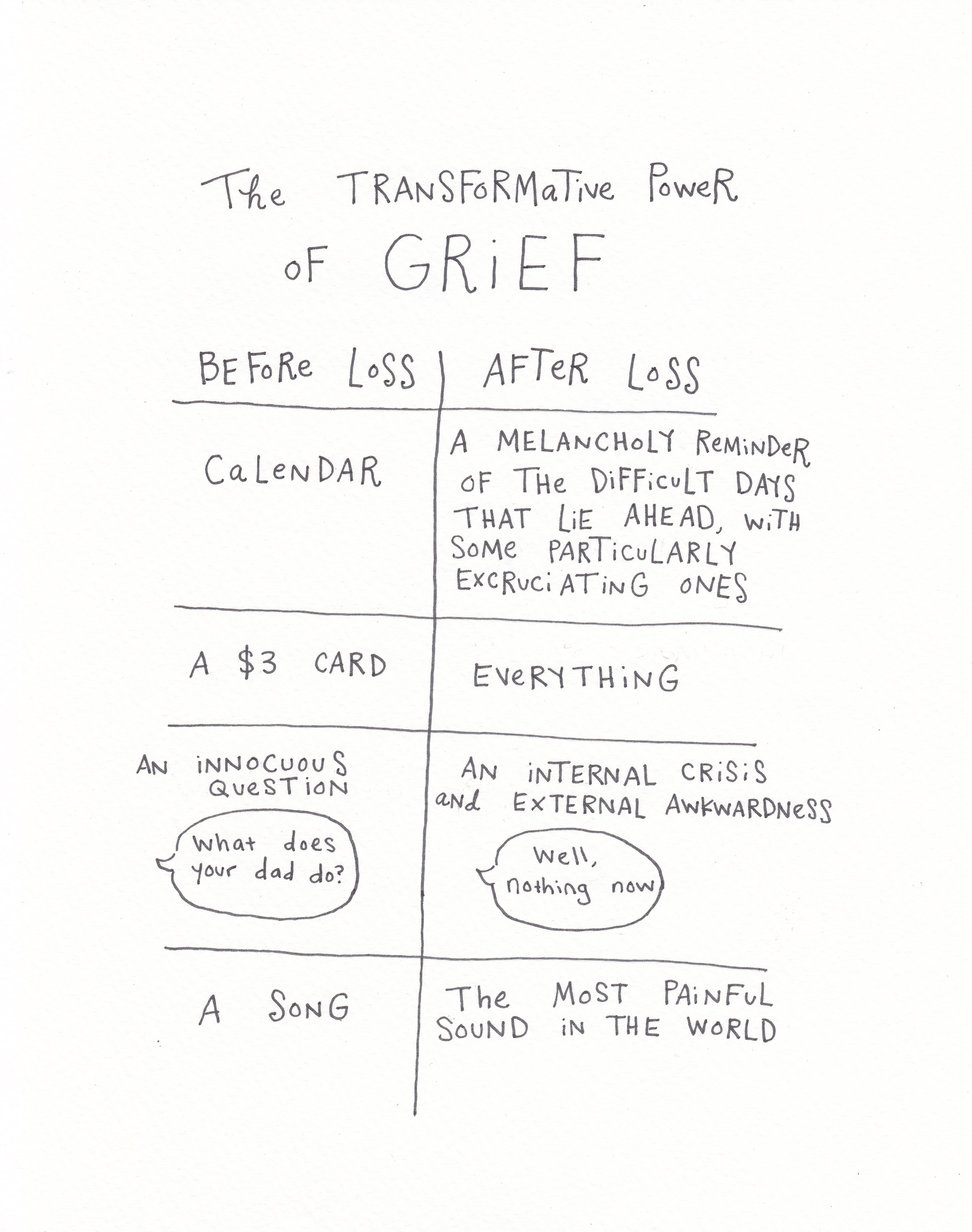

The Illustration below by Mari Andrew sums up the “transformative power of grief”, in everyday mundane thoughts and conversations: